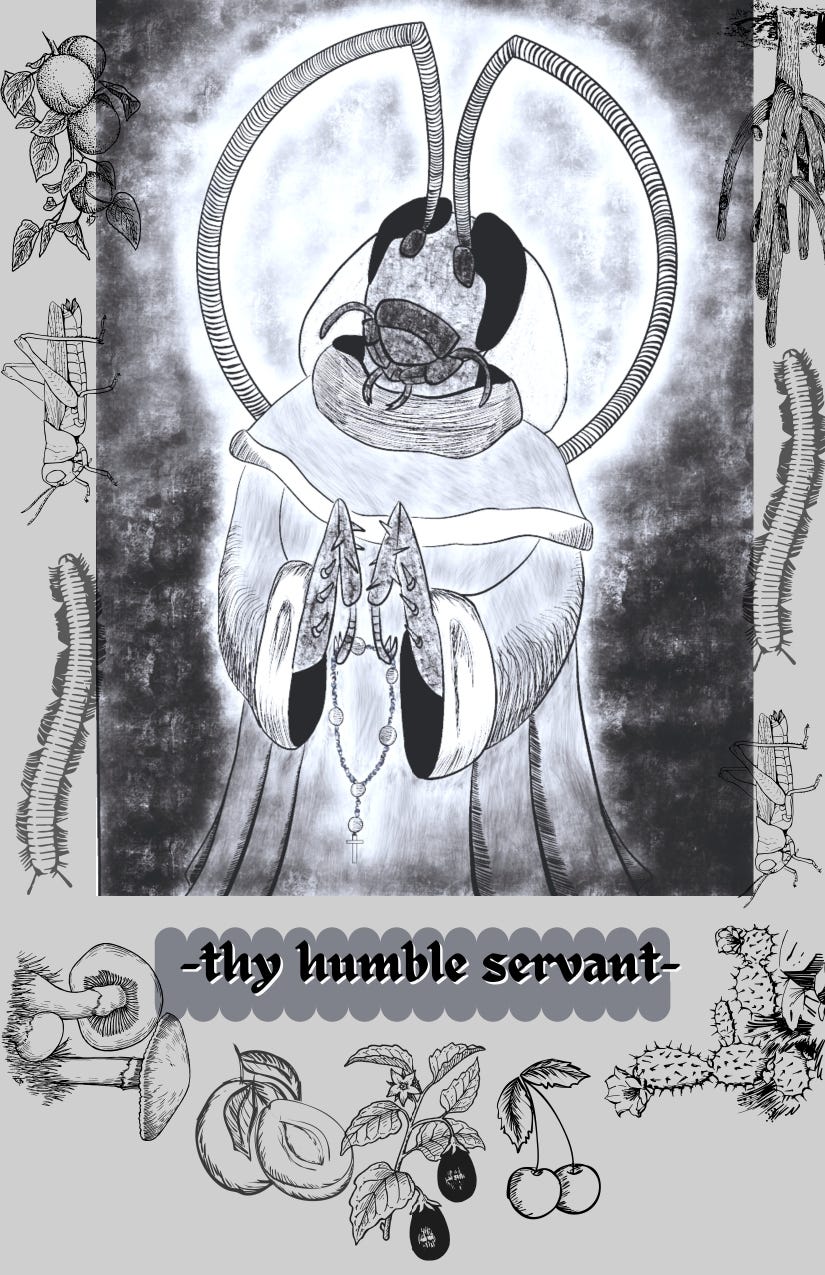

Great art is a great story. This week we’re highlighting humble servants of the worm, a compost collective based in San Diego. The group’s blending of satirized Catholic core with ecological menace has resulted in compelling branding. They also wear demon masks when they table at zine festivals, which is pretty cool.

Read on for an interview with one of their members, Fabian, about how humble servants of the worm came to be, from Zapatista aspirations to a kingdom of fertilizer. Click on the images to visit their Instagram page.

Let's start off: What's the name of your group and what do you do?

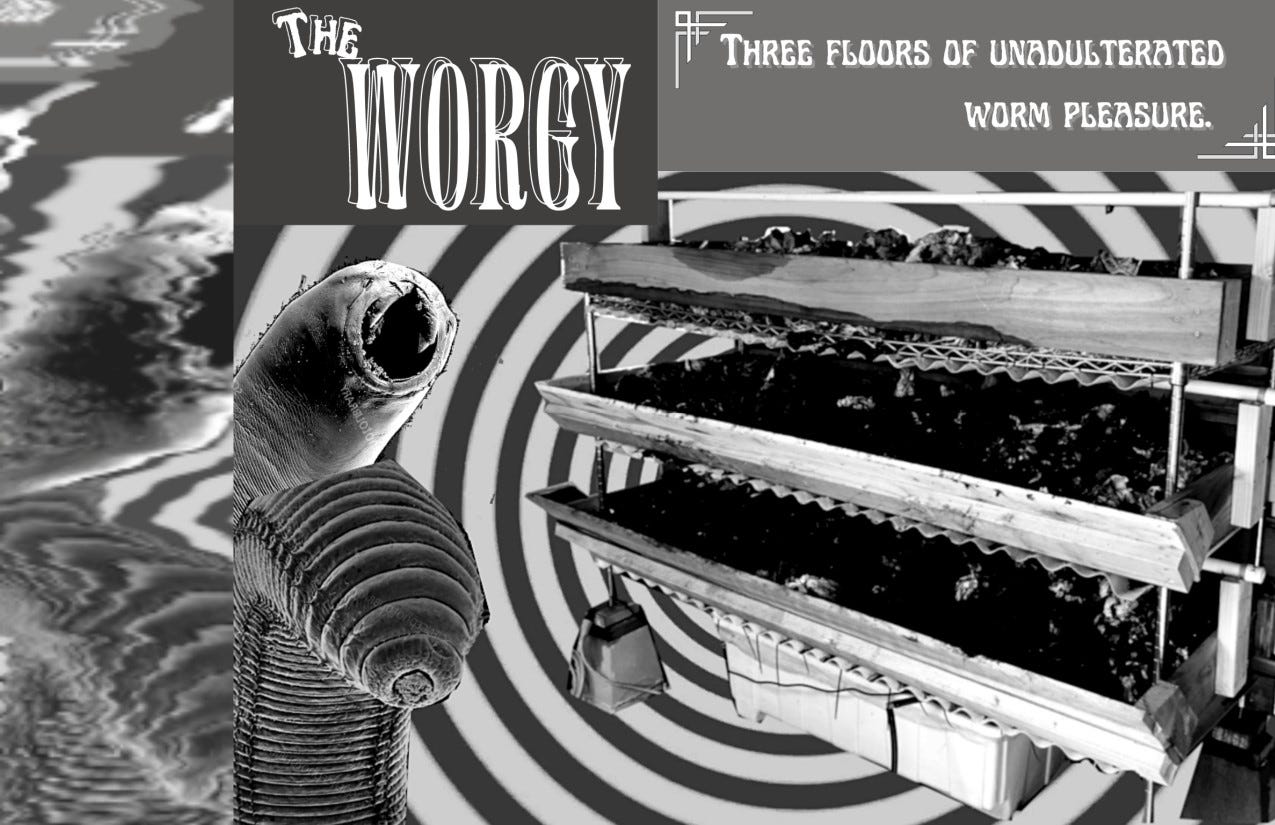

Our group is called the humble servants of the worm. We like to call ourselves a community composting collective with a propaganda problem. We came together during the pandemic as a group of folks who found that the best way to build our collective practices was through a community garden project that we started in San Diego. A group of 7 to 10 of us started regularly getting together.

Compost started taking a role a little bit later, once we realized that in order to deepen our ecological reciprocity we needed to start building the soil. We started doing community bucket exchanges. It was a free service where people would come and borrow an empty bucket and later bring back their bucket full of food scraps.

During that period, we fell into this grant that Cal Recycle was trialing, which resulted in a lot of grassroots activism that was in preparation for a state bill. The bill would require California to divert 100% of its food scraps, so a lot of community groups came together and advocated that Cal Recycle set aside funds to demonstrate that community composting initiatives could be just as effective as these industrial-scale food diversion programs.

So then we expanded our connections with different community composting groups across California. For us, from the beginning, the community element was always central. We saw the garden as a space of organizing, conspiring, sharing knowledge, and promoting this ethic of tending to our territory and developing this relationship with waste.

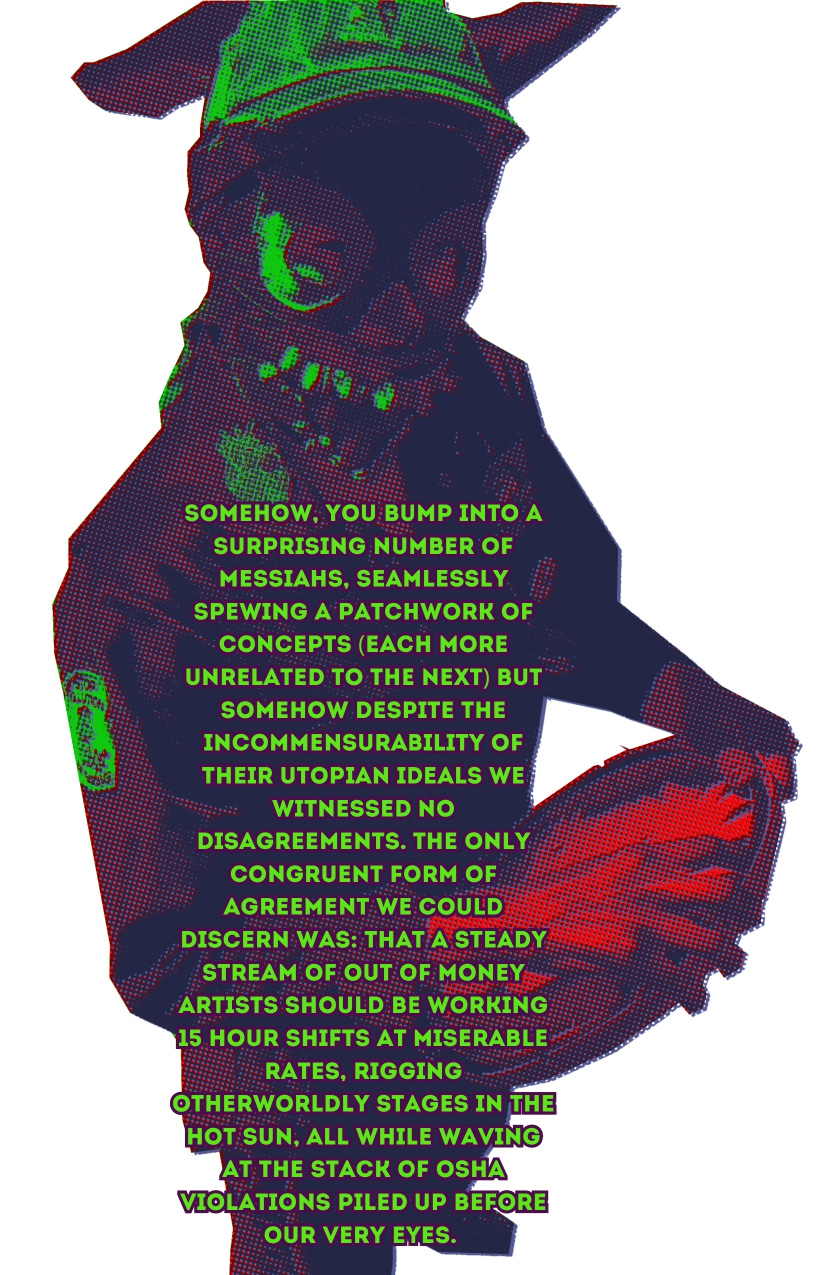

We had been doing food scrap collections around a park here in San Diego that had a variety of restaurants, and we were riding around with a big bicycle trailer full of food waste. Every time we'd move, we’d see folks setting up shop and starting these pretty unhinged Christian installations in the parks.

You'd see these huge banners that had these grotesque images of Christ and we were like, “This is nuts.” But there is something super compelling about these folks who are so deeply devoted that they occupy public space and intervene in a way that is somewhat confrontational, antagonistic, and esthetically thought out.

We started talking about how we should be doing that. We should be proselytizing in a way that's tongue in cheek and critiquing the moral economy of environmentalism. That's where we started toying with the idea of being “the humble servants of the worm” as this tongue-in-cheek inversion of the Catholic evangelical hierarchy and them thinking God is above us and we do the right thing because we fear eternal damnation.

We're already on a planet that is damned to hell. We are already living the apocalypse. Our message needs to hyper-charge this notion that the only way to survive the apocalypse is by coming together through these underground networks of scavenging through shit.

Composting became a metaphor for the kind of practice that we were trying to cultivate. And we tied the community element with the joy that came from being outside together and shoveling shit at each other and having a good time doing it.

We started tying all of these ideas together and all the while some rifts were happening with our group. As some of us broke away, the core of our organizing was, “How do we survive the apocalypse?”

Well, it's through building a project that gets land, a place where we can address our like housing issues, where we don't have to stress about rental properties and be subjugated to shitty landlords and increasing rents and other destructive relationships to the territory.

Land is central to our project. We saw this composting initiative as the mechanism that’s going to help us accomplish this. We’d build a network of allies within our territory and work towards this acquisition of land. We continued different organizing efforts with compas in Chile, across the border in Tijuana, and more recently with Bikes of Pueblo here in San Diego. We currently share a lot with them as we organize events together.

You described your group as a “collective.” I want to ask about what that horizontal structure looks like. How are responsibilities divided up in your group?

For example, you're interested in a grant. Which of you applies for the grant?

We have collective meetings during which we come to decisions through a process of consensus. So it's similar to voting where a majority has to agree. Consensus means discussing the subject until everybody is on board with the types of strategies that are being taken on.

Some of the ways we operate also include encouraging individual members with a particular interest to propose a particular action strategy. That gets talked about and the ethos is to support that kind of direction.

The process with the grant was that a couple of us who were connected to the urban farming scene had come across it. We were the ones who proposed it. We said, “We're happy to fill it out. We need the collective’s support in this way and this other way".”

It wasn't a top-down directive, but something that developed through this process of proposing, discussing, and then consensus. Division of labor is also something that we try to keep in balance. Spontaneous initiative, self-motivation, and also setting action points to try to meet those goals within time frames that we set through the discussion.

You mentioned consensus, it’s a very important part of your group. If there's conflict, how is that resolved?

So this is something that--

It’s the big question for collectives.

It is a big question. And it has come up in the past and has been the reason why there's been splits in our group. Those experiences have led to more refined strategies for dealing with conflict and coming up with mediation strategies.

Before the conflict even arises, we have this culture of communicating, sharing, and being straightforward with each other. Conflict has arisen between collectives, specifically regarding things like lease negotiations and compensating different groups. But at the end of the day, our guiding principle is that collectivity matters above all.

Even if it's something that feels really stressful and needs to get done and it's only falling on one person, the priority is to remain a collective. And if that thing has to go, or it doesn't get done, it’ll fall by the wayside.

Moving on, I want to talk about your masks and your zines. It's got this black comedy— not snark, but it’s really silly in a way that I enjoy. I'd love to know how kind of that aesthetic was reached and how that informs your messaging.

Some of the motivating elements that contributed to our aesthetic are being fans of hardcore punk music, black metal music, and other things. We want to explore death without falling into the ideological and esthetic traps that other groups, like the Norwegian black metal scene, fell into where it became a death cult.

They started burning churches and there are all of these flirtations with fascism that come as a result of the nativistic ideology that those groups took on. It’s a celebration of darkness that is actually quite sinister. Our project is not trying to think about death as something to avoid, and it's not celebrating desires for annihilation and destruction.

Humor works as a knife, that cuts through the tension, and opens up the possibility to be different, to be criticized, to change. We see the synergy between thinking about death and some topics that are really difficult and uncomfortable. This abyss of grief and horror in the West is viewed very negatively. It’s only focused on the sadness, but it encompasses a lot more. The deeper thing that is encompassed is the possibility of transformation. Humor is the tool we carry to access that wealth of possibilities and to expand that horizon.

We’ve only got a few minutes left, so I want to ask some speed-round questions. Number one, the masks: how many are there?

Right now, there's probably six or seven masks. Two of them make regular appearances and they come as a result of an event that we hold yearly called Campus Carnival. They're supposed to be an embodiment of the demons that live inside the compost pile and are threatening to turn the world upside down.

Last question of the day. What is the most that humble servants of the worm can be? In the minds of the collective, what is the peak of this group?

(Laughs) Jeez. Right now we have a medium-term goal of getting land. We are working to set up a pet composting service such that we can offer funerary services for pets so we can, like, compost them and offer the compost for restoration efforts.

Down, down the line, we want to be able to offer what’s called “natural organic reduction services” or human composting. It’s a way to think about compost as something we can offer to directly nourish the environment around us with our bodies. Ultimately, our sense is to think of yourself as compost in the making. What you put into your body is about making sure that once it passes, it can nourish something deeply without contaminating or poisoning it. ⬤

Portions of this transcript have been edited for clarity.

See more from humble servants of the worm by visiting their Instagram page.

If you’d like The Daily Egg to showcase your work in a newsletter, reach out to us! You can fill out the Artist Highlight form here, or email/DM us for more information.

[ARTIST] Cattail Curios

Great art is a great story. This week we’re highlighting Misha Morales, the illustrator behind the fancifully rendered Cattail Curos sticker collection. She explains her design process below; click the images to visit her Instagram and sticker shop.

![[ARTIST] Cattail Curios](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!QCYE!,w_1300,h_650,c_fill,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep,g_auto/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2F7f5258d8-ddf0-4459-bacb-55322d7f2970_1668x2224.jpeg)